Extant Suthar community of Bassi

The haveli, in Bassi village, where we stayed the previous night (winters of 2010) belonged to a family of Rajputs who were descendants of a Senapati, in the army of Mewars. The haveli, especially the interiors, were tastefully renovated that perfectly suited the modern day needs and comfort. The staff was equally hospitable too. The cuisine offered by the haveli ranged from local to Punjabi and other northern regions of the country. The Rajput-family – retired Major and his wife – who still occupied a portion of the compound, gave us a company over dinner, the previous evening, and filled us in with respect to general history and must-visits within the area.

Howsoever tempting, I resisted the couple’s offer to sit, around a small bonfire, for a chat over coffee after dinner.

Having polished off a heavy breakfast, we left the haveli for the interiors of the village (not to be confused with the market on the main Chittorgarh-Kota road). Most of the craftsmen work and put their crafts on display in shop-cum-houses located inside the village. Although it was quite late in the day for a market, the street market in the interior of the village was still not opened. So we headed through the narrow streets to the ancient temple dedicated to Lord Shiva located at the far end of village. The temple was situated just adjacent to an olden step-well (Baoli) as well as a pond, both of which were considered equally sacrosanct.

The wifey paid obeisance at the temple and also confirmed the location of the wooden-craftsmen houses spread within the labyrinthine lanes of the village. A majority of the locations were spread around a chowk, called Nalla Bazaar, located on the main street. Having spent about thirty minutes, enough to explore the immediate surroundings, we headed towards the chowk where a few shops had opened by now. The recently built houses, mostly painted white, in the village adopted the widely prevailing modern day architecture while quite a few of the villagers continued to reside in their renovated olden houses that still incorporated the traditional elements like burjs, chhattris, jaalis, etc. In fact the village still housed many olden buildings, cenotaphs as well as sculptures.

The village of Bassi is prominently located on the map of Kashthkar (woodcrafters) clusters set in the desert state of Rajasthan. The Major had told us that the village is famous for its woodcrafters, shoemakers, potters as well as bidi-makers. Among the woodcrafts, Bassi is particularly well-known for exquisitely prepared Kawads, a folding wooden mobile miniature-temple popularised in areas of Rajasthan both by worshipers and Kawadiya Bhat story-tellers.

Before this I had read and heard about the Bhopa community, priest singers, in Rajasthan who performed similar religious-storytelling, albeit on a much larger scale, by reading through phads, a folk painting on a long piece of cloth. In this day and age, it may not be tough for one to procure the compositions of Bhopas, especially Pabuji, in an audio CD. Whereas, in this case, much because of the medium used by them, I failed to source any of the creations of Kawadiyas in a digitally-recorded format. The chowk proved to be a near-perfect site where crafts of various kinds and varieties were put on display. As I enquired about Kawads from the bystanders, all fingers seemed to point towards one shop.

The lady prided herself with the fact that hers is one of the few families of the Kawad-makers that survive in the village today

I hurriedly approached the shop, which had just upped its shutters and was jointly managed by a couple. The husband was yet to arrive at the shop. The lady told me with pride in her eyes that hers is one of the few families of the Kawad-makers that survive in the village today. Belonging to the Suthar (Kawad-maker) community, her family has been engaged in this profession for the past 400 years. Believed to have been originated in Nagaur, her ancestors migrated to this area, which later came to be known as Bassi, as the Mewars were not only more amiable to this form of worship but offered better opportunities to the craftsmen.

The Kawads of various forms and sizes were showcased in the wooden slabs of the shop. The small portable wooden shrines had pictorial accounts of religious tales represented by Gods, Goddesses, Saints, Heroes, etc. on panels that were hinged together as doors in order. The visuals in the Kawads depicted stories from Hindu epics such as Ramayana, Mahabharata, Puranas as well as folklore. Engaged in Kawad Bachhana, storytelling orally, the storyteller known as Kawadiya Bhat, usually hailing from the areas of Marwar, takes the portable shrine to its client, the devotee or the patron, known as jajmaan, filling the sacred space as well as claiming an identity for all the stakeholders concerned with its production, expression and audience. The audio-visual renditions of the story forged a sacred alliance and synergy between the stakeholders and kept the tradition alive.

Belonging to the Suthar (Kawad-maker) community, her family has been engaged in this profession for the past 400 years

The Kawadiya Bhat (not to be confused with Kaavadiyas who carry Ganga-water before Shivaratri in some north Indian states) periodically takes the sacred Kawad to his jajmaan’s house (usually fixed and carried on for generations) for recital and receives donations in return. Although the traditional custom is increasingly losing popularity, it is believed that listening to stories, through this medium, purifies the soul.

Meeting her and learning about her profession as well as family was a notable experience. Although, with the practise of Kawad Banchhana fast losing ground, her ancestors had to take up other forms of woodcrafts such as puppets, miniatures, etc. as time progressed. We too bought a few craft items from her shop and asked for contact details at which she immediately flashed her calling card. The state government has been claiming to provide the remaining Suthars with some economic benefits in the form of popularising the art and craftsmen. At this juncture without much linear knowledge, I would rather not delve into the success or failures of such schemes. Without visiting other shops and hoping for the betterment of Suthars, we left the village and headed towards the Fort of Chittorgarh.

The Little Khajuraho

Prevalently branded as the Little Khajuraho, the Menal Temple Complex, said to have been built between eighth and twelfth century, is located almost midway on the 160km long Chittorgarh-Bundi highway-stretch in Rajasthan. It was in the winters of 2010 when I first got an opportunity to travel on this highway.

Literally meaning a Great Gorge, the Maha Nal or Menal temple was built by Chahamana Kings during the 11th century.

Having finished the first leg of our adventure-filled honeymoon at Ranthambhore, we set out for Chittorgarh to continue with our sojourn in the desert state of India. Already overjoyed with her first sighting of a Tiger in the wild, the wifey offered to navigate reading the map as well as road-signs. Unlike other regions especially a certain north-Indian states, the highways in Rajasthan are well marked with road-signs. It was this chariness of the highway authorities that saved the day for us otherwise the roadmap-books – Eicher and makemytrip – both billed as “detailed” were effusively full of errors. Both the map-books appeared to be on the same plane – of misinformation – with respect to showing a highway or a link-road connecting two destinations. Having repeatedly experienced issues with the maps on several occasions in different regions, I plan to prepare a comparative review of both the road-maps soon.

As for the road-conditions, the entire stretch of the highway right after the town of Sawai Madhopur was outstandingly favourable allowing a trouble-free drive till Chittorgarh. The traffic on the highway was few and far between. The previous night, we had identified Bassi village to be our next night-halt as it was located just a few km short of the majestic Chittorgarh Fort. The wifey was particularly interested in experiencing the hospitality of traditional Havelis of the region and the village offered just that. With their architecture borrowed from temple designs of the period as well as some Mughal-styled overtones, the renovated mansions attract constant flow of tourists and have been particularly favourite with foreigners.

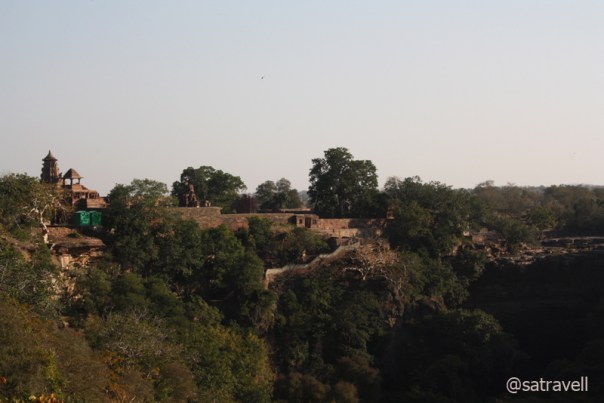

Before this, the only knowledge I had of the area was that a temple complex named Menal and famed The Mini Khajuraho exist somewhere near Chittorgarh. It was solely because the wifey decided to pursue, after reading a couple of lines about the place from the guidebook we were carrying, we decided to visit Menal. So as to confirm we were on the right track, we still preferred to take directions from the bystanders on the highway. In little less than three hours we reached Menal. The picturesque green patch is not quite visible from the highway itself. The entrance of the temple complex is located somewhere behind the roadside shops and could be reached by taking a 100/120m-motorway near the Prasad shops. We parked our car inside an imposing Marriage Palace-cum-Restaurant located just off the highway ahead of the shops. As I ventured into the backyard garden of the hotel-compound, the wifey ordered some fresh chana-chaat and lemon soda for a quick and much-needed refreshment. The view from the garden was breathtakingly splendid. The transformation of landscape from sandy-green to lush green forest was swift and seemingly encompassed well thought through elements handpicked by a photo-artist to fit into a frame.

The view from the backyard garden of the restaurant. Notice the temple complex on the left and the densely-wooded gorge on the right of the photo-frame

The ancient temples built with red sandstone in Hindu style situated aside the weathered and water eroded deep Menal gorge coated green by lush forest cover was a perfect blend of men’s desire and nature. Separated by the riverbed comprising eroded granite slabs, the poetic ruins of an ancient Palace as well as the temple complex dotted both sides of the now dry Menal. The steep rock-faces of the gorge bore marks of the flow of the Menal during rainy seasons. Green shrubbery of various shapes and sizes peppered the rock-faces as well as both the banks downstream. As regard the wildlife, currently the topography could unfortunately only afford some birdlife.

The Menal Gorge captured downstream from the temple complex. The restaurant building is also visible in the frame.

Marking the western fringes of the Uparmal plateau, famous for sandstone quarrying, located northwest of Vindhyas, the rain-fed Menal River before merging with Benas a few km downstream, create patches of densely wooded ravines that provide natural retreat from the scorching heat of the desertscape in summers. The nippiness provided by the green cover makes this place all the more attractive in the region. It was possibly for this reason that the great Prithvi Raj Chauhan chose Menal ravines to be his summer retreat in the desert state.

As if the magnetism offered by the landscape was not enough, the caretaker of the hotel had switched on the electrical fountain before I stepped in the backyard of the complex. His intention, which was not hard to recognise, was to make the visitors believe, through the sound of the fountain, that the flow of the river was perennial and not seasonal. Although, the spot receives fewer visitors, leaving aside the pilgrim-season, the complex surely commanded a well looked-after property; at least a state tourism department-run-restaurant. Having devoured the mini-snack meal, we rambled towards the entrance of the temple complex.

Approaching the admirably fabricated double-layered gateway to the temple courtyard, one passes through lawns carpeted green on both sides of the paved pathway recently built by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Having witnessed continuous raids as well as seizes ever since its inception in the 11th century, only a few structures including temples survive to this date. Administratively, the area was seized by Akbar from Mewar Kingdom and has since been beholding the apathy shown to it by successive governments. Only recently, the facelift of the complex and restoration of temples was undertaken by the ASI. Nevertheless, the temples have always been favourite with local population and pilgrims.

The imposing gateway is carved with figurines of Ganesha and Bhairaov. On the other side of it, in the stone-floored courtyard, lies a magnificent temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva, surrounded by several ruined structures. The walls, pillars and top of the Shiva temple are finely carved with sculptures of Hindu deities. A few of the structures inside the complex were built in the 8th century.

In the absence of qualified guides or signboards depicting detailed information, we failed to decipher much out of the general layout as well as its historical and cultural resemblance. For one thing was certain, the temple strictly followed Hindu-styled architecture, prevalent at that time, and was built at a perfect place that also seemed saatvik where meditation would have been more effective and meaningful. It was the architecture and rock carvings which resembled the Khajuraho group of temples.

We then headed towards the ruins of the palace and the riverbed. No sooner we stepped on the water-eroded blackened granite slabs than a swarm of couples emerged from behind the rocks and large-sized granite boulders. Our sudden presence seemed to have disturbed them!

The structures as well as temples on the other side of the riverbed were commissioned by the queen. Lord Shiva and Parvati could be seen portrayed alongside dancers, lesser-known Gods as well as elephants and other animals. Having taken a few photographs of the landscape, we sat with a pujari who filled us in with respect to the temples and the area around. A few trails, mostly frequented by locals, from the riverbed led to other areas within ravines. A short visit to the temple complex makes for an ideal morning or afternoon destination. The view of the temple-scape in the magical light of sunset made for an interesting capture.

…Afterwards, we continued our journey to reach the palatial Haveli, at Bassi, owned by descendants of the family of a Senapati who served in the army of Mewars…

Rhesus Macaque

Rhesus Macaque

Local Name: Bandar

Distribution: Widely distributed across South, Central and Southeast Asia; inhabit a great variety of habitats from grasslands to arid and forested areas, but also close to human settlements

Conservation Status: Common

Location: Sultanpur National Park, Gurgaon, Haryana, Dec 2011

bNomadic

bNomadic