Book Talk: A Mountain in Tibet

Monsoon is my favourite season after winters to enjoy reading books. Even as the much-loved seasonal rainfall continue to elude my region for fifth year in a row; so far, I have wrapped up over half a dozen books. Before getting back to sharing travel stories on bNomadic, I’d wish to share my thoughts and reactions on a few more titles I came across during all this while. The current one in line is A Mountain in Tibet, a travel bestseller written by the master travel author and historian Charles Allen.

For over three decades now, the master storyteller Charles Allen has been bringing out thoroughly researched and lucidly narrated books illuminating the field of travel writing, colonial or regional history. And just so, carrying his signature expression, this particular book packs a researched and unprejudiced narration that traces the natural history, myths, legends and information surrounding the Kailash Mountain and particularly the sources of the Great Rivers of Asia. From the astonishing geographical properties of South-Western Tibet that are celebrated in Hindu and Buddhist sacred literature to the Indian surveyor spies called the Pundits who explored it in disguise or the controversy surrounding Sven Hedin’s claims and more, the author takes an objective approach to trace the origin and true sources of the River Ganga, Sutlej, Indus and Brahmaputra in Tibet.

The book comprises ten interesting chapters; each talking about a specific period or activity related to the legend of the sacred Kailash, the queen of lakes – the Mansarovar, the true source of the Ganga, Sutlej, Indus, Brahmaputra and its course through the forgotten frontier, etcetera. Through this book, Charles Allen has tried to present a historical glance into what Sven Hedin would call, “a geographical mystery that had captured and held men’s imaginations ever since the first Aryans penetrated the great Himalayan mountain barrier some three thousand years ago”. Even as the Kailash remains the centre point of the book, the author has particularly emphasised on enticingly tracing the true sources of the four great rivers whose upper courses lay hidden in the Kailash Mansarovar region. The journey to retrace the rivers starts with description of the Mughal Emperor Akbar’s attempt to order the first systematic inquiry into the sources of India’s great rivers and fine-tunes with details coming out of the most recent satellite findings.

The author explains that the mystery around the Kailash was centred on the belief shared by a large slice of humanity that somewhere between China and India there stood a sacred mountain, an Asian Olympus of cosmic proportions. This mountain was said to be the navel of the earth, the axis of the universe and from its summit flowed a mighty river that fell into a lake and then divided to form four of the great rivers of Asia. It was the holiest of all mountains, revered by many millions of Hindus, Buddhists and Jains as the home of their gods.

The trans-Himalayan plateau of Tibet is a vast, sterile, and terrible desert, too cold and too arid to provide more than the meanest of existences. Till about a century ago, the Kailash remained an enigma to the outside world. With the onset of the twentieth century, a succession of few enterprising travellers, remarkable explorers and enthusiastic pilgrims who took up the challenge of penetrating the hostile, frozen wastelands beyond the Western Himalayas; reasoned out the mystery to some extent. Gradually the true sources of the four mighty rivers: the sacred Ganga at Gaumukh, the Indus, the Sutlej and Tsangpo-Brahmaputra in the Kailash Mansarovar region were identified.

Comprising 290 pages of full excitement, A Mountain in Tibet is available at an average price of Rs 270 at Amazon and Flipkart. I totally recommend this book to someone who is interested in knowing more about the Kailash Mansarovar region or the sources of the four great rivers.

Book Talk: The Himalaya Club

I have always enjoyed reading fiction or non-fiction emerging from the days of Raj and particularly if the book has anything to do with travel or the Himalayas to be more specific. And led by this active interest, a few weeks back, I bought this book from a popular bookshop at the Khan Market in New Delhi. Titled The Himalaya Club and other entertainments from the Raj, the book was originally authored by John Lang in 1859; a few years before he died in Mussoorie, Uttarakhand.

The book is divided into five chapters in which Lang has weaved random titbits of the colonial India British society particularly stationed in the hilly sanatorium of Mussoorie or Shimla. The Himalaya Club is just the first story of the book. Sarcastically weighing the social life of the British community, the author skilfully talks about the scandals, flirtations, adulterous relationships, gambling through cards or billiards, ego-related duels or quarrels, hierarchical disputes and disciplinary commands, etcetera. Lang’s description does portray a realistic picture of the hill town’s social life along with the typical differences of the social and travel life of Mussoorie and Shimla (Simlah) during those days.

The next story Military Matters satirically depicts the farcical proceedings of a court-martial trial. The story The Himalayas talks about Lang’s babu-style travel to Almora (Almorah) along with his two European friends. The Returning features civil court cases involving Indian under-trials at the Magistrate’s court of Bijnore. The author highlights corruptness of the system where occurrence of injustice and unfairness was a commonplace. A man was sentenced to death for committing a murder in place of his prosecutor who was the real murderer.

Going by the title of the book, I was hoping to find a good deal of information related to the natural history of the Himalayas or at least the initial adventurous pursuits of the British or Indians. Save for the story The Himalayas that describes their super luxurious game-hunting travel to Almora, another hill station occupied by the British at the time of writing, there isn’t much in the book to look forward to from the perspective of the Himalayas. The book might be of interest to someone who wishes to read about page three talks and party gossips of the hill stations of Mussoorie and Shimla.

The foreword of The Himalaya Club, which is possibly its only saving grace, is penned by the much loved author Ruskin Bond. In his typical nonpareil writing style, Ruskin Bond, himself a resident of Mussoorie, narrates just how he learnt of John Lang and his works. Quite venturesomely, Bond later successfully discovered Lang’s burial site in an old English cemetery at Mussoorie. John Lang was born in Sydney, Australia in 1816 and was among the first from that land to set foot on the Indian mainland. Other than being an elusive writer, Bond describes Lang to be a master barrister who represented Rani of Jhansi in her legal battles against the East India Company.

Anyhow, the 135 page slim book does provide a humble overview of the social life of colonial India. Mannerism, dubious actions, doublespeak and such habits form the undercurrent of the book. I bought this book at an undiscounted price of Rs 199, however, the same is available at a current average price of Rs 145 at Amazon and Flipkart.

Book Talk: A Hermit in the Himalayas

Last few days have been very hectic on the work front. Travel stories from whatever I could manage in-between will follow soon but before that I wish to share my thoughts on an evergreen Himalayan classic A Hermit In the Himalayas written by the eminent travel and spiritual writer Paul Brunton. Shuttling between travels and assignments over the past few weeks, I got a good deal of time to savour this book written by the man who was among the first to champion the Himalayan spirituality and Yoga in western world.

The sultry summer heat of May and June is an unlikeable period to inspire spiritual wisdom in the mind. Nonetheless, the book provided me with inner rewards and a subconscious dose of Himalayan-induced spirituality; making up for the loss of not being in the lap of the Himalayas. Honouring his journalistic as well as traveller’s instincts, the author does talk about the harsh clamour of contrasting cultures, politics or fates from across the globe but, indeed, much of the book is about the spiritual beauty of the grand solitary spaces of the Himalayas.

The book was first published in the year 1937, during which time, the author travelled extensively in the East particularly Indian and the Himalayas in search of peace and spiritual isolation. It is but natural that much would have changed in the world since Paul wrote this book but at the same time many things continue to remain the same particularly the calmness of the Himalayas and politics of its kingdoms. Hoping against the hope of securing a permission to visit the Sacred Space of Kailash Mansarovar in Tibet, the author, Paul Brunton sojourned in comfortable yet peaceful confines of a forest bungalow in a wooded hillside of Tehri in Garhwal, Uttarakhand. Although he failed to conquer the diplomatic hurdles to visit Tibet, he nevertheless met the celebrated Kailashi Swami Pranavananda as a visitor to his forest home who narrated his perilous journey to Kailash Mansarovar through Kashmir and Leh.

Compulsively fond of drinking tea, particularly the one he obtained from Darjeeling, he turns his expression towards nature; penning every simple thought coming out of a hermetic retreat in the Himalayas. Brunton relates his communion with various dramatic elements of his Himalayan abode; from the silence of a starry night to reading constellations, from soaking in the Deodar air to confronting a leopard, from exercising self-control to the efficacy of Yoga, from giving first-aid to a sheepherder to counting icy peaks and mountaineering expeditions, etc. And yet he accepts the importance of a city life,entertainment, of concrete jungles with equal ease and need. The underlying theme of his discourse in the book is to seek “a pathway into the deep stillness of our higher self through scared communion with nature itself”.

Embodying the grand forces of nature, the Himalayas he believes, “are an oases of calm in a world of storm”. Sweetened by the love emanating from the Supreme Being himself, the pure Himalayan air revitalises the soul. The mountains are flushed with beauty that belongs, not to them, but to God; leaving us with an inspirational poetic symbol. “The steep paths of the Himalayas are akin to the steep paths of life itself. But I adventure up the rugged trail with music sounding in my ears. God is luring me on”. Calling the Himalayas to be his novitiate for heaven, he adds that in these grand solitudes I may prepare myself for the sublime solitude of God.

In about 190 pages, the book captures the author’s spiritual takeaways from the Himalayas in an expression that suits a spiritual journal. Like most Europeans, he too travelled in a typical British babu style. Preferring to not isolate himself from the world around in real sense of the word, he kept an orderly to assist him in his mountain life where he was in constant touch with the outside world through letters and notes or even visitors.

I suggest this book for every Himalayan lover. Read this to feel the beauty, clarity and solemn silence of the godly icy mountains; in words. The book is currently available at Amazon or Flipkart at an average price of INR 382.

Weekend trek to Churdhar

Not many people would have noticed that an open conical snow-covered peak is visible from Chandigarh on clear winter days. Foregrounded by the Kasauli and Sirmaur hills of Shivalik Range, the peak is distinctively noticeable from the plains of Chandigarh. Bearing a romantic name of Chur Chandani Ki Dhar or the mountain range of silver bangle, this is the nearest snow-peak to the national capital territory of Delhi. Referring to the glittering snow, the intriguing Himalayan feature of Churdhar humbly holds snow for more than seven months of the year and is visible from the hills around Mussoorie and Shimla as well as from the plains of Chandigarh and up to Saharanpur.

I recently climbed this grand peak in rather spontaneous circumstances. Aman Sood, the founding member of Chandigarh ByCycle and my partner in crime on most such outings asked me to join him on this trek on one fine weekend of recent autumn. Even while doing our post-graduation at the Panjab University in Chandigarh, we would often see the Choor (as the Britishers used to call it) and admire it; the first peak of prominence rising above the Shivaliks. Having budgeted a week-full of free time to explore the Rajgarh Valley, we planned a quick trek to Churdhar, a ridge popular for religious as well as historical values offering quite moderate approaches.

The road to Nohradhar, the base station to attempt Choor from southern side. Nohradhar is 70km from Solan via Rajgarh. More images at Flickr

The peak of Churdhar is accessible from many approaches but the popular and safest ones are northern one from Chaupal and southern one from Nohradhar at 2160m. We were keen on climbing the peak through its southern face from the base located at Nohradhar. We self-drove from Chandigarh to Nohradhar via Rajgarh, a bumpy ride on a popular orchard trail of the state. The trail to Churdhar begins adjacent to the PWD Rest House (2191m), where we parked ourselves. In the evening we took a few acclimatisation walks around that area and the main market. Calming down the gusts of dust and heat coming from the plains, the valley of Nohradhar is fairly wooded where orchard economy is valued over grains. The market is very basic but the supplies necessary for the trek could still be sourced. A few locals have converted their house into guesthouses for visitors like us. Depending upon the facilities they offer, a room should be available from Rs 500 to a thousand including basic dahl, chapatti and rice meal. Planning to start early the following day, we slept earlier than normal.

Valley view from Nohradhar. Please visit Flickr Photoset for more images of the region

Next morning at 0730hrs we began our steep climb to the ridge above the settlement of Nohradhar and then proceeded along this gentle and lightly wooded ridge to reach the first popular campsite at Jamnala, also referred to as doosri. Part of a religious trail, the various rest sites on the route as we climb higher are known by pehli (2422m), doosri (2885m) and teesri (3258m), popularised by locals. These are also the sites where you could have a refill of water from fresh mountain springs. I’d recommend carrying good quantity of water with you from Nohradhar itself if you are not prepared to drink the spring water of mountains. Refraining from creating any further plastic on the mountains, we carried our bottles from the base and kept topping them up on the way from such streams; which is what I suggest. It took us nearly three hours to reach Jamnala at 2885m where a couple of enterprising families from Nohradhar had put up a seasonal dhaba providing a fixed menu of rice, dahl, tea and biscuits at a slightly premium rate. Surrounded by tall deodars, the Jamnala meadow is at a sunny spot and offers excellent camping grounds as well as water facilities. We took full advantage of the salubrious charm of the site and took a nap after polishing a plateful of dahl and rice.

The initial part of the trail; before pehli. Please visit Flickr Photoset for more images of the region

Inching ahead on the trail. Photo by Aman Sood. Please visit Flickr Photoset for more images of the region.

Taking a small break at pehli; the upper reaches of the habitation ends here. More images at Flickr

The entire stretch of the trail from Jamnala to teesri passes through a wooded section of the ridge where spotting Himalayan birds and infrequent wild animals becomes easier. I was lucky to come face-to-face with a male Himalayan Monal as also a Himalayan Griffon. Unlike the stretch from the base to doosri, where you steeply gained 725m over a distance of 6.7km; this stretch from doosri to teesri is relatively easier on the gradient. In about a couple of hours’ time we covered a distance of 4.9km to gain 373m and reach the windy campsite at 3258m. From teesri, 5.5km of distance spanned over an altitude gain of 384m takes you to the summit at 3647m.

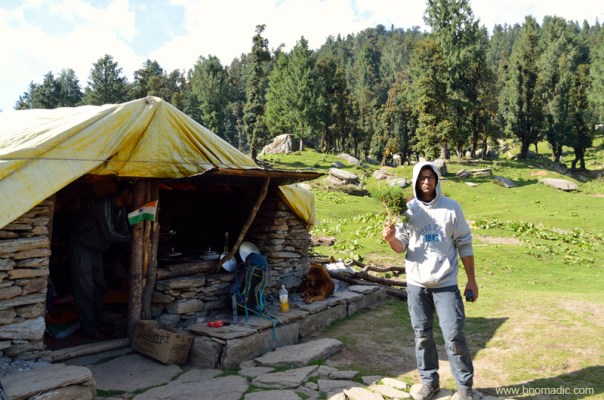

The doosri campsite, called Jamnala. More images from the region at Flickr Photoset

At 2885m, Jamnala is a good campsite insofar as availability of water is concerned. More at Flickr

Napping at Jamnala. The paper cup in the frame was properly disposed of at Nohradhar and not at the campsite

Himalayan Griffon Vulture. More at Flickr

Taking a short rest in a wooded patch of the climb between doosri and teesri. More at Flickr

Smitten by the mountains, the Himalayas. More images from the region at Flickr Photoset

Intending to complete the trek over a weekend, many people prefer to halt for the night at teesri meadows but being on a curved part of an exposed ridge from both sides, it can be really windy to put up own tent. Save for the availability of water nearby there isn’t much comfort insofar as a campsite is concerned. And in case you plan to stay inside dhaba owner’s hut, be prepared to face mammoth-sized rats. But then the views! From here we could see right up to the Kullu Himalayas including its lower peaks and the prominent Deo Tibba as well as Indrasan. As we sat admiring the panoramic view, we met Panditji who introduced himself to be a farm owner at Nohradhar and a member of the Chur Devta committee, which looks after the affairs of dharamsala and the temple. Having munched on a maggi, biscuit and tea diet outside a makeshift seasonal dhaba in a shepherd’s hut, all of us headed towards the temple dharamsala located a little below the summit.

The teesri campsite on the ridge at 3258m. More images from the region at Flickr Photoset

Scheme of things inside the dhaba at teesri. Please visit Flickr for more images of the region

View towards the south from teesri campsite. More images from the region at Flickr

View towards the north from teesri meadow. Please visit Flickr for more images of the region

Just 1.1km ahead of the teesri at 3310m is the last point before the dharamsala where you could refill your bottles with water. For the first couple of kilometres from teesri, the route takes a gentle gradient to climb after which it steeply ascends to reach the temple. This is of course the best stretch of the entire route; scenic as well as easy on the go. As the gradient becomes steeper and boulders appear, the route bifurcates into one that leads straight to the summit through its south face and the other one skirts the ridge to approach the summit through its north face via the temple. The direct route is shorter by a kilometre but is very steep and exposed. We took the longer one that passes through a boulder strewn mountain-face, which made our going even more tiring. The boulders and humungous outcrops of granites of course bear a testament to the geological riddle of the Himalayas.

A meadow just ahead of teesri. This is of course the best stretch of the entire route; scenic as well as easier.

A couple more mounds to be crossed before getting to climb the final ridge located further afar. More at Flickr

Panditji and a group of pilgrims resting at the last water refill site ahead of teesri against the backdrop of the Choor

Just before the route bifurcated; one route climbs straight up and follows the ridge line to reach the summit located towards left of the ridge while the longer one follows the treeline from above, gradually finding its way to reach the peak from behind i.e. north face. In the pic: Aman taking notes

As we slogged our way ahead, Panditji told us stories and anecdotes about the region and the religious importance of Chureshwar Mahadeo, an incarnation of Lord Shiva and the guardian deity of the Churdhar. Even though, the trail is more frequented by pilgrims than adventure seekers, the mountain has been popular with both including natural historians. Located in the watershed of the Sutlej-Yamuna, this region has been popular with adventure enthusiasts since ages. Even as George Everest stationed himself on this peak to survey the heights and reach of the Himalayas, the maharaja Yadavindra Singh of Patiala popularised water sports through his activities in the river Giri, located west of the mountain. The climbing records of Choor have references of British expeditions from 1820s.

At the west-end of the Choor‘s south-face. More images from the region at Flickr Photoset

Facing north after skirting the final ridge. More images from the region at Flickr Photoset

Taxing the knees, our traverse through the rocky crags and boulders was more frustrating than the windy gushes. Wild flowers of all colours and curious shapes popped up from among the stones. By six pm, just in time to witness one of the most remarkable Himalayan sunsets, we made it to the rocky slab above the temple. It was a stunning place to be to soak in an awe-inspiring Himalayan wonder. For the first time I saw the Great Himalayan spectacle at sunset right from Kullu and Kinnaur to Garhwal. The peaks of beautiful Swargarohini and the Bandarpunch that had eclipsed the peaks of Gangotri region looked distinctively golden.

Fading light at Churdhar. Please visit Flickr Photoset for more images of the region

The Swargarohini Massif glittering in the golden light. More images from the region at Flickr

Landscape a few minutes later. Please visit Flickr Photoset for more images of the region

As it became darker, the pilgrims made a beeline towards the dharamsala that remains operational throughout the pilgrimage season. The facilities at the dharamsala are most basic and don’t expect more than a mattress and blanket to spend the night. The best part is that you can get a meal plus potable water if you knock at their doors at right time of the season. Otherwise, there is no dearth of camping space on top. The air we inhaled was clear and blessed by the Himalayan spirits. That night, apart from Sirmaur region, we could see right up to the lights of Mussoorie hills and Doon Valley that seemed just a few minutes away.

Daybreak at Churdhar. Please visit Flickr Photoset for more images of the region

Atop the summit of Choor, above a compilation of rocks and slates rests a statue of Lord Shiva that adds the required five feet to make it a 12,000 ft peak, the nearest snow-capped mountain to Delhi. Photo by Aman Sood

Next morning as I woke up and began to pack our gear, Aman had already made a return from the summit of Choor that offered a remarkable 360 degree view of lower Himalayas. Above a compilation of rocks and slates, a statue of Lord Shiva adds the required five feet to make it a 12,000 ft peak. The view wasn’t as free of haze as we had expected it to be. Shimla hills lay to the northwest and the Ghaggar plains to the southwest. Observed from the top, the lesser ridges appeared to be arid in contrast to the wooded patch we had hiked through yesterday. Far in the distance, the Great Himalayan Range majestically stood above everything else on the way.

Aiming to reach the base at Nohradhar before the sunset, we started our descent by 1000hrs. Even as the descent was more taxing on the feet and heels than the ascent, we were down to Nohradhar by 1900hrs in the evening. Back in the room, the same evening, we met with a local political leader who reciprocated to our greetings from the Choor. We were happy to have finally climbed the peak from where the Mughals used to source ice to keep their imported wines chilled during the summers in Delhi.

Beginning the descent to Nohradhar; north-faced in current frame. With the Great Himalayan Range in the backdrop, the other popular trail that leads to Chaupal is also visible on the lower ridge

Above 3000m, the trail is carpeted with variety of Himalayan wildflowers. Photos by Aman Sood

The trail downwards; this dog accompanied us throughout the trek. More images at Flickr Photoset

Inside the dhaba at Jamnala; our tea is brewing. More images from the region at Flickr

First sign of habitation after pehli on the descent. More images from the region at Flickr Photoset

Another hour before we reached the base at Nohradhar. More images at Flickr Photoset

Yours Truly at a fruits shop after the trek. Photo by Aman Sood

Trek Summary:

Total distance: 17.5km (one way)

Time taken: Two days with a night on top

Base (2160m) to Pehli (2422m): 2.5km

Pehli to Doosri (Jamnala) at 2885m: 4.2km

Doosri to Teesri at 3258m: 4.9km

Teesri to Temple at 3454m: 5.5km

Temple to the Peak at 3647m: .4km

The Impregnable Fort of Kangra

With a week-full of activities in the lower foothills of Kangra region behind us, we decided to explore the Fort of Kangra, which was the seat of power of the rulers of Kangra during ancient times. Standing on the Kangra – Hoshiarpur highway, as one looks up the towering mass of the fort spread on a precipitous cliff and listens to the gurgling of water and the whistling of wind in the Banganga gorge 300ft below, one cannot help but be wonderstruck admiring one of the most impressive fort ruins in the country.

The Fort of Kangra above Banganga and the Jayanti Devi temple in the backdrop. More images at Flickr

The locals take great pride in the historical importance of their fort, which is indeed a testament of great power; and are never tired of boasting about its impregnability. Both its location and fortification entitle the Fort to be called impregnable by historians. Perched atop a cliff that droops vertically to the Banganga and Manjhi rivers, the Fort commands an extensive view of the Valley. Reachable only through a narrow piece of land, the Fort is secured by a series of gates later named after its conquerors ranging from Jahangir to Ranjit Singh and even the British.

The Fort is currently under the control of the ASI but the royal Katoch family also continues to operate parallely through its office towards making the fort visitor-friendly. At the entrance gate, the audio guides made available by the Katochs radioed their version of the interpretation of the history of Fort. Although, the Fort is said to have been founded by an ancestor of the Katoch Rajas, Susarman, who was also an ally of the Kaurvas in the battle of Mahabharta but the historians have only been able to confirm its origin to the early medieval period based on currently available “direct evidences”.

The ASI ticketing counter and main entrance of the Fort. More images at Flickr Photoset

The Fort from near the main entrance. Please visit Flickr for more images of the region

The Ranjit Singh Gate. Please visit Flickr Photoset for more images of the region

Aman and Sarabjit studying the details of the gate and fortification wall. More at Flickr

As one approaches the fort through the main entrance adjacent to the ASI museum, an imposing gate associated with Ranjit Singh leads to a protected enclosure. The fortification wall is strikingly fitted with protective features like platform for guards as well as slits for sharpshooters at its back. Ahead, the ascent to the main section is protected by another line of fortification wall beyond which yet another gate secures entrance to the initial platform. Called the Jahangir Darwaja, this is said to be the earlier outer gate of the fort from Hindu times and as Alexander Cunningham pointed out in 1875, its original name was still now known.

For its strategical position in the foothills north of prosperous Punjab, the Fort of Kangra had its full share of the vicissitudes of the history of north India. Then known as Bhima Nagar after the pandava Bhima, the Fort was conquered by Mahmud Gazhni on his fourth expedition in the year 1009. Mohammed Tughlaq conquered it in 1337. Jahangir visited the valley via Siba and Guler in the winters of 1662. The Fort remained in the possession of the Mughals till 1783 after which a Sikh chieftain Jai Singh Kanheya captured it. Four years later, the Fort came under the possession of Sansar Chand who became the supreme ruler of the Kangra Valley. In 1809, the Fort was occupied by Ranjit Singh after which the British took over. As the British left the valley, the Fort remained neglected for a long time until it came under the management of the ASI.

The topmost platform of the Fort, the core area, is secured by yet another line of fortification wall. This platform is approached through a gate facing the Jayanti Devi temple on an opposite hilltop. After passing through a small gate, we reached the innermost courtyard where once stood the palace of the Rajas, which is now in ruins. The courtyard contains the temples of Lakshmi Narayan, Ambika Devi and a Jain temple with a stone image of Adinath which is more than five centuries old. Covering the ruins like a giant umbrella is a Bodhi tree which is said to be very old. Although much of the original fortification is now in ruins as seen elsewhere in this Fort but it is here where the destruction of the April 1905 earthquake could be observed more visibly.

Gateway to the main courtyard. More at Flickr

The main courtyard inside the Fort complex. More images from the region at Flickr Photoset

The amalakas and other debris in the courtyard. Please visit Flickr for more images of the region

The surviving wall of the Lakshmi Narayan Temple, one of the most impressive structures inside the Fort.

Among the abundant traces of structures nearby, a stone-lined well and the shapes of some multi-roomed structures along with some freestanding pillars could be spotted. More at Flickr

Some more ruins adjacent to the courtyard. Please visit Flickr for more images of the region

Within the courtyard a number of amalakas along with other broken remains were strewn around on the ground. Among the abundant traces of structures nearby, a stone-lined well and the shapes of some multi-roomed structures along with some freestanding pillars could be spotted. Bearing the brunt of the earthquake, the surviving walls of one of the most impressive structures in the Kangra Fort, said to be the Lakshmi Narayan temple stand on a raised platform that makes it nearly impossible to understand its original layout. The top of the Fort lies further up and is approached by a series of steps from adjacent to the temple ruins. With everything in ruins, not much could be gathered on the top apart from a wide ridge and wide open valley views. Located close by towards the main market of Kangra, the ancient temple of Vajreshwari Devi also attracted the attention of invaders, just as the Fort.

The topmost section of the Fort. Please visit Flickr Photoset for more images of the region

Atop the Fort; with the development of modern artillery, forts may have lost their political importance but remain a picturesque reminders of the feudal past or a preferred haunt of young couples as in this case.

View across the Manjhi Gorge. Jahangir was so fascinated by the beauty of the Valley that he desired to build a summer residence there. The foundations of a palace were actually laid in village Gagri, close to Kangra. The work was abandoned, as later he preferred Kashmir. More at Flickr

The crumbling walls of the Fort and the Banganga down below. More images at Flickr Photoset

Some select rubble from the Fort lined outside the ASI museum. The sculptural friezes were inset in the walls of the structures inside the fort.

As we sat lunching at the cafeteria outside the main Fort complex, we mused over the fact that how colourful and rich the culture of Kangra must have been in its heydays. The café was managed by the royal Katoch family of Kangra as also a small museum and an arts gallery within the same complex. While the famous paintings and Kangra art was practised in the foothill towns of the valley such as Guler, Tira Sujanpur, Alampur and Nadaun, etcetera, the Valley was also famous for producing fragrant rice, sugar and jaggery. Deriving its origin from “kan-gra” or the ear-shapers, the Valley of Kangra was the ancient destination for surgical operations related to restoration of noses and ears by surgeon community called Kangheras.

Paintings and cuttings at display inside the Royal Museum. More images from the region at Flickr

bNomadic

bNomadic