Prelude

The following post is a part of the “Kailash Mansarovar Yatra” Blog Series Into the Sacred Space. To read complete travel memoirs and trip report, please visit here.

The road to the Sacred Space. Straight and unbending. Much like truth. Captured from a point between Lhatse and Zhongba. Please visit Flickr Photoset for more images of the region. Photo Credit Aarti Saxena

The first glimpse of the crystal clear waters of Lake Mansarovar and the sparkling snow of Mount Kailash convinced us that the deepest sources of inspiration and motivation are tucked away in the folds and cracks of the mighty Himalayas. This was the reason, we realised, that since time immemorial the best of yogis, sages, saints, and explorers, had undertaken the gruelling climb up the forested ridges or snowy caves of the Himalayas in order to meditate in the midst of the divine presence here.

A rare overcast weather day in the trans-Himalayan region. Captured from a point near Gala. You may like to visit Flickr photoset for more images of the region. Photo credit Aarti Saxena

Spread over the secluded highlands and positioned miles away from the humdrum of noisy cities, lies what we now believe to be the place where God’s presence can be experienced most tangibly. Nowhere else have we meditated under skies that are bluer, breathed air that is cleaner or seen colours that are so vibrant, bright, pure and abstract. Here, the landscape itself appears like an eternal expression of prehistoric forces.

As it marks the watershed of South Asia’s greatest rivers, the Kailash Mansarovar region has fascinated generations for centuries. Till the late nineteenth century, it was believed by almost one-fifth of humanity that somewhere between China and India there stood a sacred mountain, said to be the navel of the earth and the axis of the universe. This region was considered to be ‘the most significant and magnificent geographical problem’ still left to be answered on earth before the arrival of the previous century, writes Atkinson in the Himalayan Gazetteer, his record of developments related to the Himalayas.

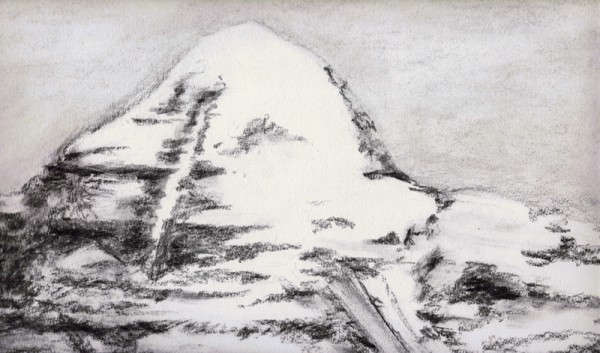

The mighty Kailash. In its mystical form, this isolated holy mountain, 6638m in altitude, is known as Meru; in its earliest of manifestations it was Kailas – the ‘crystal’ or in local parlance Kang Rinpoche – jewel of snows.

Many an attempt were made by the powers that be including the British, Germans as well as the Mughal emperor Akbar to solve this geographical mystery. For centuries, legend had it that there was a mighty river that arose from the summit of Mount Kailash and flowed into a lake which gave birth to the four of the great rivers of Asia. Umpteen attempts were made to map this region and trace the true source of the four rivers that originated from the Kailash watershed as well as the channel between the Lake Mansarovar and Lake Rakshashtal. It finally took more than five centuries to establish the true source of these four great rivers, namely the Sutlej, the Indus, the voluminous Brahmaputra and the Karnali, a major tributary of the Ganga River.

The Kailash and Mansarovar region is believed to be the holiest of all pilgrimages in more than four religions. In its mystical form, this isolated holy mountain, 6638m (or 21,778ft) in altitude, is known as Meru; in its earliest of manifestations it was Kailas – the ‘crystal’ or in local parlance Kang Rinpoche – jewel of snows. The Hindus believe Mount Kailash to be the abode of Lord Shiva, the supreme creator and destroyer. For the Buddhists, the sacred rock is the place where the world and all its powers originated. Followers of Jainism believe that it was here that the founder of their religion achieved enlightenment. The ancient shamanistic Bonpos who pre-existed Buddhism in Tibet believed that the holy mountain provided a link between heaven and earth and drew powerful cosmogonic, theogonic and genealogical associations from it. On a religious map of Asia, if it ever existed, most of the lines identifying the main pilgrim routes would focalise at this remote and remarkably sacred region in Western Tibet.

Literally meaning Lake of the Demon, the Rakshastal as observed from the ridge that separates it from the Lake Mansarovar. For more images of the region, please visit Flickr Photoset.

Accessing the region has never been an easy affair as the Kailash and its waters lie enclosed by the toughest and most inhospitable of natural barriers on earth; the Himalayan ranges to the south and west, the deserts of Takla Makan and the Gobi to the north and east. In addition, due to its own inwardly-directed religious preoccupations, Tibet had for centuries – until 1959 – remained sequestered from the world outside. Select traders and pilgrims were allowed after careful investigations but other explorers, particularly westerners, were strictly prohibited.

Nevertheless, few spirited and courageous trans-Himalayan travellers made a name for themselves by venturing gearless into the forbidden land. Such a feat, however, required nerves of steel and a strong measure of rebelliousness to overcome the natural as well as manmade impediments. Having read about the works of Indian surveyor-spies called the Pundits who explored the Tibetan mainland in disguise, the controversial claims made by Sven Hedin, the military mission of Younghusband to Lhasa, the scientific research work of Swami Pranavananda, our interest and desire to visit the true iconic figures of the Himalayas had grown manifolds.

Mostly directed by the desire to satiate the obvious curiosity and fascination, we had embarked on the journey to the holiest of natural shrines. For both of us, who prefer to travel (and live!) without a fixed itinerary or objective in mind, such a meticulously organised sojourn was going to be a new experience. As our vehicle inched its way towards the sacred region through the inhospitable terrain of Tibet, we couldn’t agree more with the fact that its raw countryside is the ultimate overlander’s delight in terms of the scope for adventure and excitement. Perhaps not anywhere else on the planet is it possible to travel in the shadow of peaks, eight-thousand metre high, and cross multiple high-altitude mountain passes most of which are above 5000m.

Vasant Bhatol taking a stroll along the shore of the Lake Mansarovar. More pics from the region at Flickr

Now that we are back and as we write this with deep interest, we haven’t been able to disassociate ourselves with the breath-taking grandeur of those two iconic figures, which we call the Sacred Space. It is as if we’ve had a sacred communion with an infinite strength, wisdom as well as righteousness. The subsequent posts will portray our experience, observations and inner echoes in the light of the foregoing description. We were fortunate to be a part of the group that was full of humour, knowledge as well as religious quest. The distance between New Delhi and the Sacred Space, as the crow flies, is just 475 km compared to above 6500km we covered to complete the journey through the Nathula. Honestly, we rate this Yatra among the most mind-stimulating organised travels in the world. Towards this, we also owe our gratitude to the Government of India, Government of China, MEA, STDC and concerned officials who made it possible for us to visit the dreamland, the Sacred Space.

Into the Sacred Space

It was a cold misty morning at Nathu La, the natural high-altitude passage between India and Tibet, across the Himalayas, in Sikkim. Passports had been verified for the one last time by the Indo Tibetan Border Police Force (ITBP), baggage tags checked, and the visa papers secured, as the rain came down lightly on the first batch of the Kailash Mansarovar Yatris standing in a straight file at the Indo-China border, some 4,310 m feet above the sea level. These thirty seven pilgrims were witnessing history being made before them by being the first travellers from India to enter the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) through the Nathu La after the border was closed in 1962.

We, the members of the first batch, or the historical batch as the authorities would tell us over and over again could feel the unmistakable excitement and festivity in the air. Having dreamt of a Kailash-Mansarovar visit all through our lives, we were finally heading to the most sacred spot on this planet to almost half of humanity including the Hindus, the Buddhists, the Jains and the Bonpas.

“One mountain, however, stands high above the rest, a sacred mountain overtopping the ranges of lesser sacred mountains, their epitome and apogee. This mountain is called Kailas.” – John Snelling. The Kailas sketched by Aarti Saxena

The mountains had always fascinated us. “The Godly Kailash and the Manas-Sarovar (translated as ‘the mind-lake’), how placid and beautiful could a lake be whose name sounded so heavenly?” such thoughts kept us occupied. We had all heard stories or anecdotes of the Kailash visit from those who had been to the holy land. Some experienced yatris in the group would often share their tales over meals and acclimatization walks from day one of the yatra.

“Yea in my mind these mountains rise, Their perils dyed with evening’s rose;

And still my ghost sits at my eyes. And thirsts for their untroubled snows”

Swami Pranavananda quotes Walter De La More in his memoirs

We were fast getting initiated into a direction that would eventually take us into the deep stillness of our inner-self by way of sacred communion with nature. Away from the madness of the cities, we had never felt more alive than when we were in the embrace of the Himalayas. Inside our minds, the mystical yearning to visit the Holy Kailash Mountain and the Mansarovar Lake in Tibet had been germinating for many years. The very thought of such a possibility would leave us dreaming about the grand solitary spaces of the Himalayas. The moment when our yearning of years was going to be fulfilled had finally arrived. It filled us with great delight when our wish and desire to pay our first homage to this natural and divine wonder through Nathu La got materialized in June 2015.

This blog series is a joint effort by Aarti Saxena (who also happened to be the Liaison Officer of the batch) and Satyender S Dhull, who were blessed to have been a part of the first batch of the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra (KMY) via the Nathu La. As we write this with deep contentment of finally having visited the Holy Land, we cannot help but wonder still if we shall ever be able to visit Kailash again. For us, our spiritual-escapade into the Sacred Space would always be a rare adventure in Tibet, a country absolutely full of history, interest and significance.

There are no mountains like the Himalayas, for in them are Kailas and Manasarovar — From the Skanda Purana. Watercolor on paper by Aarti Saxena

The following posts are an endeavor in capturing the most magical moments of the yatra, before and after we crossed the Tibetan border! We hope you enjoy reading about our journey and experience it through our eyes and perspectives. Om Namah Shivaya!

Disclaimer: All views expressed here are personal, and do not represent the views of the Government of India in any manner.

From Plains to Sikkim (New Delhi – Bagdogra – Teesta – Rangpo – Gangtok)

Reception at Gangtok (The Ridge – 15th Mile)

Adjusting to Higher Altitude (Gangtok – 15th Mile – Chango Lake)

The Legend of Soldier Saint Baba Harbhajan Ji (17th Mile – Kupup – Jelep La)

Crossing Nathu La to Enter Tibet (Nathu La – Yadong – Phari – Gala – Kangma)

Getting Shepherded through Tibet (Kangma – Gyantse – Friendship Hwy – Shigatse – Lazi)

By the Yarlung Tsangpo Chu in Tibet (Lazi – Saga – Zhongba)

Traversing the Barkha Plains (Zhongba – Paryang – Barkha – Darchen)

The Kailash and the Yam Dwar (Darchen – Tarboche – Deraphuk – Zutulpuk – Darchen)

A Glimpse of Eternity by Mansarovar (Darchen – Barkha – Mansarovar – Qugu)

Retracing the Trade Route to Nathula (Qugu – Zhongba – Saga – Lazi – Shigatse – Gyantse – Kangma – Yadong – Nathula)

The Festivities Around (Nathula – Sherathang – Gangtok)

Back to the Plains (Gangtok – Darjeeling – Siligudi – Bagdogra – New Delhi)

Book Talk: Himalayan Playground by Trevor Braham

“How wonderfully fresh and adventurous it must have been for the 20-year-old Braham travelling through the Himalaya in 1942 as a young soldier on leave during the Second World War and how wonderful to have Sherpa companions whom he had read about in the pre-war Everest expedition books,” pens the ace mountaineer Doug Scott in the forward written for the book Himalayan Playground by the author Trevor Braham. In a way his expression sums up what this book is all about – the adventures of Braham from 1942 to 1972 on the roof of the world – the Himalayas.

Having spent a good part of his studentship in Darjeeling during the British Raj, energetic Trevor Braham took to mountaineering at the age of 20. The blessing guardianship of the Kangchenjunga massif had casted a strong influence upon him that aroused his later ambitions in the field of organised mountaineering. His initial rambles in the western part of Sikkim in 1942 enabled him to define his interests and helped him assess his strengths and limitations.

Next he boarded the thought of Garhwal Himalayas in 1947 and climbed the Kedarnath Dome among his many other exploits in the region. Opportunely he was in the holy town of Badrinath, as he claims, on the day when India gained independence. “It was a privilege to have visited the mountains of Garhwal at a time when unlimited mountaineering opportunities existed in a beautiful and practically untouched region,” Braham writes. Himalayas addicted, he visited the Himalayas almost every year during the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Braham’s other noted explorations recollected in the book includes that of Sikkim region in 1949, Kullu-Spiti watershed region in 1955, Karakoram in 1958 before his interest shifted to the tribal regions of Swat, Kohistan and Kaghan during the decade of 1960s. According to him his prime objective of traveling to the mountains was not to seek material objectives or accolades but in search of those eternal rewards that only Himalayas possess, free from the routine humdrum of life.

Although, the book sheds some light on the mountain life of the times about which very little written historical evidence has been obtained, it essentially remains to be a recollection of the events that transpired more than 50 years before. Written in 2008 without any seeming aid from the trip-reports, the book fails to do full justice to his raw enthusiasm, interest as well as the variety of information otherwise obtained by way of travelling into the regions which were relatively untouched by mountaineering or tourism. Frankly speaking, the book is merely a recollection of his experience giving a blueprint about his “trips”. The description in the book looks to be mellowed down after a gap of more than five decades.

Notwithstanding the loss of information, the book intriguingly captures climbs in the remote Himalayan region by way of trip-photographs. Without doubt, one of the most interesting aspects of this modest book is the description of his activities in the tribal areas of Pakistan Himalayas. Although, it makes for a pleasant read for a Himalayan lover, nevertheless, nearing Rs 2000, a paperback edition of the book is highly overpriced. The book is available at Amazon as well as at Flipkart.

Book Talk: Jim Corbett of Kumaon by DC Kala

“A tiger among men, lover of the underdog, a hero in war and pestilence, a model zamindar and employer, an ascetic, naturalist, and, above all, a hunter of maneating tigers and leopards for thirty-two active years in the then three hill districts of Uttar Pradesh comprising Garhwal, Nainital and Almora,” is how the author DC Kala aptly introduces the legend of Corbett in the opening lines. “Others hunted but he also wrote,” adds Kala.

Anyone who has read his books will be able to relate with how justly Kala chose to describe the legendary Jim Corbett. This is the first book I read about Corbett which was authored not by him but an admirer and a fan of his, DC Kala, formerly a news editor with the Hindustan Times. Born and brought up in the hill region of Kumaon, Corbett’s birthplace as well as his workplace, Kala fully utilised the opportunity to unearth every possible information to decode Corbett, through systematic spadework, within his reach. Writing a biography is always a tough job in the sense that one has to rely on most accurate set of information. In this case, his subject Corbett and all his associates had left India for good and were no longer alive when the author started writing this biography of Jim Corbett in late seventies.

In absence of any written record, apart from letters or agreements exchanged by Corbett in his professional capacity, the author has relied on the information gathered from various secondary sources including Corbett’s publishers, servants’ families, Nainital’s municipality records, churches records, official orders, historical records, a few communication exchanged here and there, newspaper edits and diaries or notes left by his former colleagues, etc. One particular interesting source on which the author counts very heavily has been the thirteen pages of unpublished notes of Ruby Beyts dictated by non-other than Corbett’s sister Maggie herself. Apart from this most of the information or conclusions have been drawn from Corbett’s own published accounts of his endeavours in the wild.

In 14 chapters spanned over a total of 160 pages, with deep interest in his subject, the author has lucidly captured Corbett’s childhood, family life, his railways days, life and professional assignments in Nainital, his compassionate bonding with villagers, superstitions he had interest in and came across, his jungle sensitiveness, his works as an author, his ambitions and views with respect to wildlife conservation, his days and life in Kenya, etcetera.

Having honed his forest telegraphic skills in the jungles of Kaladhungi, Corbett grew up to be one of the finest sportsmen of mid-century India. Ironically, though, the conservationist started his life felling forests and hunting wild animals. His multifaceted career spanned over a variety of professions or streams including railways, municipality politics, churches, property dealer as well as farming. “The rest of the time he kept watch on all the bad tigers and leopards of the high hills and the adjoining plains”, writes Kala.

“These big, bad cats, maneaters to be precise, were Corbett’s extra charge. When one was proclaimed a maneater by the district authorities, they turned to him for help to rid them of it. When the call came, the 40pound tent, the suitcase and the bedroll were hurriedly packed by sister Maggie, the porters were collected, and the hunter set out in forced marches of twenty to forty miles a day – depending on the urgency – to the dak bungalow nearest to the last reported kill”.

Apart from courage, “Corbett was blessed with an excellent memory, good sight, a sound constitution, and a keen power of observation and hearing“, observes Kala. In later years, when he abandoned the rifle for camera, Corbett felt that while the photograph is of interest to all lovers of wildlife, the trophy is only of interest to the individual who acquired it. The book throws some insightful light on Corbett’s vision with respect to wildlife and forest conservation. The book includes a few black and white photographs and a map as well. Priced at Rs 250, the second edition of the book is available at most online shops including Amazon and Flipkart.

Book Talk: The Sacred Mountain by John Snelling

As apparent from the title and book-cover itself, “The Sacred Mountain” is a travel manual to the holiest of mountain regions – the Kailash Mansarovar – located in Tibet trans-Himalayas, which is regarded sacred by followers of no less than four religions of the world – Hindus, Jains, Buddhists as well as the pre-Buddhist shamanistic religion of Tibet, Bonpos. Unlike most other books belonging to the genre of travel writing, this one is not really a travel-account but a comprehensive summary of the various historical records available pertaining to travels to the holy Kailash region. The findings are presented in light of the current happenings, as regards the time when the book was first published in 1983, with reference to the unfailingly shifting religious as well as political interests.

The 2006 reprint by Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt Ltd of the second edition (1990) of the 450-page-book

Awestruck with the spirituality associated with the Himalayas, the author decided to visit the Everest Base Camp and ultimately the Kailash. “One mountain, however, stands high above the rest, a sacred mountain overtopping the ranges of lesser sacred mountains, their epitome and apogee”. “This mountain is called the Kailas”, writes John Snelling. Without digressing much into his travel accounts, the author examines the spiritual and mythological associations of the holy Kailash in the context of its historical, religious, political and geographical perspectives.

The author narrates the accounts and findings of the relatively few known Western travellers and explorers who managed to reach the remote Kailash. The interface of westerns with the locals not only brings out the cultural differences but specifically points out their individual experiences starting from Jesuit missionaries Desideri and Manuel Freyre who visited the Kailash in 1715 to Major T. S. Blackney, Strachey, Hearsey, Francis Younghusband, William Moorcraft, A.H. Savage Landor, Ryder, Rowling, Charles Sherring, mountaineering attempts of Longstaff and Sven Hedin, etcetera are of special interest. It is, however, surprising that the author gives little mention or bantam gravity to the findings of Indian visitors including the likes of Pundit Nain Singh who had non-pilgrimage exploratory interests in the region.

Justifiably so, John Snelling also delves into the accounts of pilgrims or saints who travelled into the area to satiate their religious interests. Apart from religious knowledge, such travellers including Swami Pranavananda, Swami Satchidananda, Swami Tapovan and the westerner Lama Anagarika Govinda, etcetera usually brought a plethora of cultural as well as practical information for travelling into the region. The author was particularly enamoured by Swami Pranavananda who authored multiple volumes and provided scientific data for later research. To this day the works of Swami Pranavananda, out of print now, continues to be among the best written accounts of Kailash Mansarovar travels.

It is of interest to note the accounts of various such travellers to the Kailash and understand how the spirituality associated with the sacred region and the testing, difficult as well as the dangerous journey had affected them from the exploratory point of view. The book neatly highlights the interface of travellers with Tibetan officials, who were usually hostile to Westerners, monks, dacoits in the cold and barren land as well as their exploratory and adventurous efforts both in highlighting the holy region and reaching the treacherous terrain. Finally, the author also evaluates other sacred mountains of the world with a view to bring forward the ancillary religious or semi-religious associations related to various religions of the world. The author has listed a detailed bibliography and a general set of travel information to the holy land.

Although the author has frankly accepted in the very beginning that a lot of water has passed under the bridge since I originally wrote The Sacred Mountain, the book remains to be a master compendium of Kailash Mansarovar travels. Priced at Rs 995, the India reprint of 1990 edition, comprising numerous coloured images, is readily available at most online shops including Amazon and Flipkart.

bNomadic

bNomadic